The Face Behind the Modern Kitchen: Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky

“In 1916, no one would have conceived of a woman being commissioned to build a house—not even myself.” – Grete Schütte-Lihotzky, 1997

With Women’s History Month comes the challenge of fitting billions of under-recognized innovations in research, activism, art, education, and any field imaginable into a 30-day span. One of the great beauties of History Months is that there is always too much to celebrate. However, there are several feats of female engineering and design that we appreciate every day, maybe without knowing it at all. Your kitchen– with fitted wall and base cabinetry, an electric oven, maybe some tile backsplash action– is based on a design by a female architect, the first of her kind, who broke all the conventions of her time to make it.

The Impact of War

The war had claimed three million lives throughout the country. Towns were devastated, buildings and homes fell into disrepair, and families floundered with 15% of the country’s men fallen. Unrest and revolution railed on, culminating in the abdication of the Kaiser. The land shrunk, claimed by surrounding countries, taking almost half of Germany’s iron production and a large proportion of its coal production with it. Imports of food and necessities were blocked and stalled; food became a luxury. The debt accrued by the Great War would take 92 years to pay off.

In 1918, if you lived in a German city, your day would likely begin in squalor. The most common housing for an average working family was tenement housing called Mietskasernen, or rental barracks. These were two-room dwellings: one room generally served as a space for more special occasions, such as Sunday dinners, and the other served as a bathing area, a kitchen, and a bedroom. Germany was in dire need of new housing that would affordably improve quality of life and cater to the needs of working families, so as to resolve housing shortages and dissuade greater unrest. Housing projects cropped up all over Germany, but one in particular left an impact that still shapes our kitchens today.

The First Female, Austrian Architect

After becoming the first female student at the Kunstgewerbeschule (presently the University of Applied Arts Vienna), Grete Schütte-Lihotzky went on to become the first female Austrian architect. Ernst May, city architect for the New Frankfurt project, noticed Schütte-Lihotzky’s award-winning functional designs for social housing in Austria and sent for her to join his team in Frankfurt, where she would go on to invent the Frankfurt Kitchen– the first fitted kitchen, and the basis of all modern kitchens today.

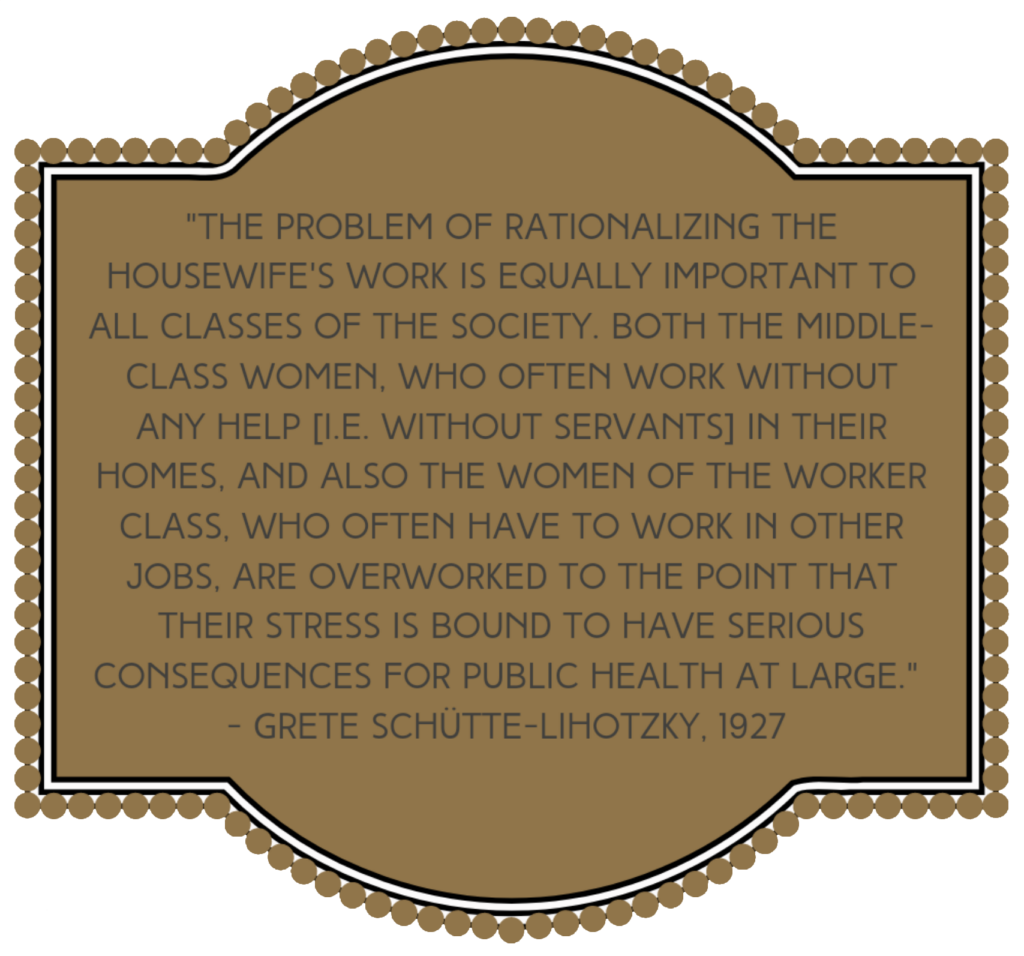

Schütte-Lihotzky conceptualized the ideal kitchen space to, among other things, have functional clarity. Her experience alleviating the abysmal conditions of social housing in Vienna revealed to her the horrors that were all too common. Misuse of space in the cramped apartments and outdated sanitation standards both culminated in an environment that was particularly distressing to the mothers and housewives who predominantly worked in these spaces. In addition to her studies of Taylorism– the optimization of scientific efficiency in the industrial sphere, as in factories– and Christine Frederick’s publications applying these principles to the home, Schütte-Lihotzky conducted thorough time-motion studies with women’s groups and housewives to base her designs off of real issues and obstacles.

The First Fitted Kitchen

The first fitted kitchen stood out in part for its use of pre-manufactured cabinetry and for the way it used cabinetry at all. By and large, uniform cabinetry was not something people had in the 1920s– for most, freestanding kitchen furniture was the only kind to exist, and the only place where one would see cabinetry like Schütte-Lihotzky incorporated into her design was an army kitchen or a train dining car, both of which served as inspiration. The introduction of wall cabinets streamlined storage while keeping floor space uncluttered, which would have been extremely luxurious after relying on freestanding furniture like dressers to house all necessities. However, to make these kitchens affordable for about 10,000 German families, (and to simplify the process of installing 10,000 kitchens), the cabinetry was built beforehand and easily put together onsite. Sound kind of familiar? This would have been brand new in 1926, but Cabinet Joint has since made it into an art.

Making the Kitchen an Effective Workspace

Several other implementations of Schütte-Lihotzky’s designs ensured household tasks went by as quickly and simply as possible. She incorporated unintrusive workstations that served multiple purposes, such as an ironing board that unfolded from the wall, and a small butcher block-type table area where someone could mince onions just as easily as they could sit and shuck corn for several hours. Drawers labeled for common ingredients cut time one would spend walking around, and time spent walking around was cut by the consciously narrow, close-knit layout of the kitchen.

Knowledge and research on sanitation had been heavily changing over the fifty years prior to the first world war, and the conditions of the Mietskasernen were long overdue for an upgrade. It was more widely known during the 1920’s what was making people sick, such as the kitchen slash bathroom combination.

A Lasting Impact

Despite the empirical nature of some of Schütte-Lihotzky’s proposed solutions to common hygiene issues– such as blue-finished cabinets purported to ward off flies– such remedies embraced by the Frankfurt kitchen were not disproven1 until over two decades later. Even during WWII, blue cabinets were proposed to be instated in army kitchens and hospitals all over as a solution to pesky flies. Some other state-of-the-art sanitary features of the Frankfurt kitchen were the oak wood drawers for flour and other ingredients to repel mealworms, the removable waste drawer that today finds itself a luxury feature in kitchens, and beech countertops that would function like a butcher block and not easily be scratched, stained, or affected by acids. In 2023, similar hygienic ideas are still novel and sought after in kitchens.

Wellbeing as Part of Design

One of Schütte-Lihotzky’s concerns was the mental well-being of those who lived in the spaces she was designing. Pops of bright colors, such as the blue or blue-green of the cabinets, and natural light, were included to brighten up the room. Additionally, the choice to include inset cabinetry in many kitchens was an interesting one as inset cabinetry is a traditional fixture in American heritage, but we at Cabinet Joint understand the allure of durability alongside elegant, tailored looks. A good strong frame and a door carefully tucked flush inside absolutely would have catered to the efficient and life-affirming look Schütte-Lihotzky was going for.

The Frankfurt kitchen has been widely debated since its creation nearly 100 years ago. Though some have proposed that the kitchen was actually more stifling to women than liberating– arguing that a narrow passage that only allows for one person at a time effectively traps women into the kitchen and prevents household chores from being done by two people at once– the kitchen design has remained relevant as it still provides the basis for most kitchens today, quaint and spacious alike. Each kitchen with built-in wall and base cabinetry, stowable storage that makes the most of space, and a tiled backsplash, all tailored perfectly to your kitchen, is a nod to the woman who pioneered a space that stands the test of time.

Schütte-Lihotzky set out to improve the lives of those she saw struggling in Austria and Germany and ended up starting something that would bring enjoyment and ease for generations. Lasting and spreading across borders through wars and conflicts, The Frankfurt kitchen is just a piece of Schütte-Lihotzky’s legacy as an architect, an important symbol all the same of the power women have to change the world to be as we wish to see it, even if it’s by doing something we see as small. And, if you find yourself today wanting to change your world bit by bit– perhaps you want to make one of your spaces more efficient, stylish, and up-to-date– we know some gals.

1 Waterhouse, D.F. “The Effect of Colour on the Numbers of Houseflies Resting on Painted Surfaces.” The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization, 22 September 1947, p. 65.